Coastal Shacks

I have just read a fascinating new book entitled SHACK LIFE: the survival story of three Royal National Park communities, by Ingeborg Van Teeseling (New South publishing 2017). It is supported by a section written by Geoff Ashley, a heritage consultant, on the architecture of the shacks.

I am attracted to this book for three reasons. First, as a child I visited one of the shacks “owned” by my uncle, Keith Chandler. He was a returned soldier from WW2 and often invited family to help carry items down the steep track to his little holiday paradise by the sea at Era. Many years later, I had the opportunity of taking visitors to see the Aboriginal site and the magnificent natural features of this area. Second, this book offers a comprehensive and beautifully illustrated review of an area in which a dedicated community over several generations (“shackies”) struggle to retain what they see as a significant part of Australian coastal culture and social history. And third, it represents another example of how political and bureaucratic forces respond to community pressure leading to different outcomes in different states.

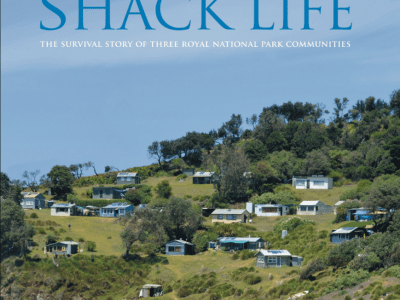

Shacks occur in three locations within what is now the Royal National Park: Era, Burning Palms and Little Garie. They are spread out amongst the trees on hill slopes protected from wave erosion, but still with stunning views of the sea. As described by David Hill, ex-Chair of the ABC and a frequent visitor, in his Foreword to the book: “Most of the shacks are very basic and the settlement has no roads, or cars, or footpaths but only rough beaten tracks”. Miners from Helensburgh were the first to build shacks although it is quite clear that the area has had a long history of occupation by Indigenous people. The miners paid rent to a farmer long before this particular area became a national park. During the Great Depression there was further construction of shacks representing what the Australian National Heritage Trust has described as an example of “depression architecture”. Similar structures were built along other parts of the Australian coast during this period.

Van Teeseling has taken an interesting approach to presenting the story of shack living and holiday visitation. She interspersed historical accounts with personal vignettes. Many of the characters who built, or later occupied the shacks built by others, were interviewed and their story told. Some of these folk are in their 90s and have endured much hardship, not just from natural events such as bushfires, but from their often difficult and costly encounters with government officials and politicians. Over the decades they have been involved in Landcare and surf lifesaving as part of communal activities. One of the recent pillars of the community is Helen Voisey. She spoke of her father who became the inaugural president of the Protection League in 1945. This was set up to fight for what shackies regarded as their rights to occupy (own?) the land on which their shacks had been built for their use and pleasure. This League continues to play a major role.

The book goes into considerable detail on the encounters between shackies and the National Park Service (NPWS) who were supported for the most part by environment Ministers. This is a classic case of social conflict with two opposing value sets that pitted protection of environmental values against protection of cultural heritage. NPWS received support from the environment movement arguing for removal of the ugly shacks despoiling nature’s beauty and biological integrity. The shack community were aided by the heritage authorities. Disclosure of legal advice on occupancy rights became a big issue involving lawyers and attempts at mediation. This has gone on and on, even while many shacks have been removed. Yet the community lives on under arrangements with the Park Service. Perhaps the next crunch date will be in 2027 when the Minister of the day can decide to accept ownership of the shacks or not.

The story of shacks in NSW contrasts with what I know of the history in Tasmania and South Australia. This is something worth more detailed research. But in NSW successive governments have not made life easy for occupants of shacks especially those in the Royal National Park. Whether the shackies are owners or tenants or whatever of the land on which the shacks are built, they have been seen as alien to the environmental values of this coastal park. In the other states, the occupants had a very different impact on government and have secured through legislation freehold possession.

Words by Prof Bruce Thom. Please respect Bruce Thom’s thoughts and reference where appropriately: (c) ACS, 2017, posted 13 May 2017, for correspondence about this blog post please email admin@australiancoastalsociety.org

#78