Orrin Pilkey: Celebrity Coastal Geologist

On 18th December, the Sydney Morning Herald posted a lengthy obituary from the New York Times on the death of Orrin Pilkey aged 90. It was somewhat of a surprise to see this in the SMH. But it was an excellent reminder of the fate of our beaches in many areas unless we appreciate their ambulatory nature and potential exacerbating impacts of climate change.

For decades Orrin was on a public mission to make Americans more aware of the consequences of building structures adjacent to beaches. He saw a challenge in making people think (knowing that many did not want to hear) that beaches belong to the people not to those who chose and were allowed to build structures next to them. Beaches are dynamic and should be allowed to move as driven by natural forces. This view drove his life as an educator, scientist and advocate for the public good, reinforced in more recent decades by an appreciation of multiple adverse impacts of accelerated sea-level rise on built structures attacked by waves.

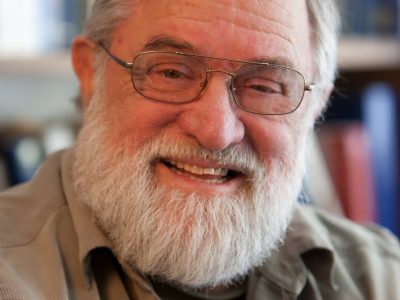

Orrin was the classic “stirrer”. Gilbert Gaul in his 2019 book “The Geography of Risk, Epic Storms and the Cost of American Coasts” stated that “Pilkey is a short, square hobbit of a man, with an unruly gray beard and a disarming sense of humor. Depending on your point of view, he is either a prophet or the antichrist of the coast”. Orrin was not offended when he saw this and said it was right! And he continued to stir with numerous media engagements.

Hurricane Camille battered the Mississippi coast in 1969 damaging his parents’ home. This proved to be a lightbulb moment leading Orrin to a career change from deep-sea marine geologist to coastal geologist. Moving to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina in 1975 he became absorbed by issues arising from what was seen as the “New Jerseyization” of the Carolina coast. This involved the building of homes, hotels and condominiums close to the active beach by removing protective dunes and building sea walls and groynes. He was particularly concerned over the fate of the barrier islands that form the Outer Banks in North Carolina. By 1978 he was ready to publish the first of several books on the theme of living with the shore (“Currituck to Calabash” with his engineer father, Orrin Pilkey Sr., Stanley Riggs and William Neal; a substantially revised version appeared in 1998 entitled “The North Carolina Shore and Its Barrier Islands: Restless Ribbons of Sand”–Duke University Press– with 7 co-authors including Riggs and Neal and granddaughter Deborah, a graduate engineer).

These are remarkable publications which received wide circulation. They clearly demonstrate how Orrin’s views of coastal change and management have been influenced by what he and his team observed over the years on this fragile coastal landscape. Over the 20 years since the first book these shores were impacted by several hurricanes and nor’easters (and ongoing sea level rise). But despite additional understanding of coastal development risk they state with a level of frustration: “People still want to build their homes in flood-prone areas, either out of ignorance or perhaps arrogance. The taxpayer-at-large is still picking up the tab now billions of dollars rather than millions and people still remove forest cover, level dunes, block overwash, or otherwise interfere with natural systems and contribute to worsening the impact from natural processes”. There is a significant increase in detail on the 1998 maps of the Outer Banks showing hazards such as where inlets have migrated, and risk zones for different sections of the coast including assessment of historic erosion rates in m/yr. The books also provide information on the “law and the shore” and advice on building and retrofitting houses near the shore. All this adds up to “Living by the Rules of the Sea”, the title of a separate book by Bush, Pilkey and Neal (Duke University Press,1996).

In 1996 Orrin and Katherine Dixon published a very controversial book “The Corps and the Shore”. Here was a clash of philosophies regarding coastal management. They stated up front that “Standing at the forefront of the struggle between people and the sea is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers”. This organization uses federal funds to build seawalls, nourishes beaches, dredges inlets stabilizes entrances with long jetties, and gives permission to others to do such things. “Strange but true, the future of the American shoreline is not in the hands of a natural resource agency but in the hands of an agency run by the U.S Army” (Pilkey and Dixon, 1996, p.xi). The book contains examples of what the authors saw as project failures to protect property and to provide for a sustainable beach through sand replenishment. In particular there are criticisms of the use of numerical models such as SBEACH and GENESIS and the assumption of profile of equilibrium published with colleagues elsewhere (e.g. J. Coastal Research,1993, 9, 255-278; see also Shore and Beach, October 1998, 2-4). Underpinning criticisms of numerical methods used by the Corps (and other coastal engineers) was the exclusion of an array of important variables in numerical model formulation; from their perspective “The large number of variables in the coastal system raises the possibility that the coastal system is numerically indeterminate…If the beach is an indeterminate system, it is impossible to accurately model its behaviour” (Shore and Beach, p.2). It’s all so complex!

In the Pilkey and Dixon book there is reference to the work of a so-called field engineer from the Gold Coast, Sam Smith. Sam is quoted as saying he never actually sees, feels or senses any of the beach process assumptions so widely used by the U.S. mathematical modellers (p. 71). He monitored beach behaviour in the field and thus was able to inform management based in his local understanding while still recognising how little he knew. This picks up on concerns by Orrin on how modeling “trivializes complex and poorly understood processes” but the down-to-earth engineer must still make decisions like Sam based on data and site experience.

This reminds me of my own encounters with Orrin, first on 3rd February 1999 when he visited Sydney University to give a seminar arranged by Andy Short, and then visit Coogee and Bondi beaches. At the seminar we heard strong criticism of methods for calculating beach needs including nourishment by the Corps of Engineers. He showed little interest in discussing alternative approaches raised during questions by several of us including a well-known NSW Government coastal engineer, now retired. Peter Cowell joined me on the trip to Bondi. Orrin was perplexed to learn that the sand in front of this 1920s sea wall had not received any significant nourishment. We tried to explain the behaviour of sand movements with closed – as distinct to leaky – sediment compartments subject to longshore drift with which he was more familiar.

In 2006 Peter and I had another opportunity to engage with Orrin (and his colleague Andrew Cooper) following publication of our paper (with Jones, Everts and Simanovic) on “Management of uncertainty in predicting climate change impacts on beaches’ ( J. Coastal Research, 22, 232-245). Pilkey and Cooper responded (22, 1577-1579) to our approach saying no amount of statistical maneuvering can accommodate the uncertainty inherent in understanding of coastal processes as the magnitude, direction and duration of the range of factors that influence coastal response to sea level rise all remain unknown. We had to reply (22, 1580-1584) arguing that we represented a tradition that seeks to organise qualitative understanding of complex coastal change problems through a systematic framework that provides a quantitative exploration of potential coastal changes in specific cases. It was a debate worth having but doubt if it had any impact on Orrin.

Bruce Thom

Words by Prof Bruce Thom. Please respect the author’s thoughts and reference appropriately: (c) ACS, 2025. For correspondence about this blog post please email admin@australiancoastalsociety.org.au

#271