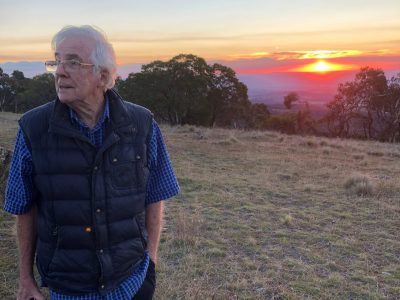

Bruce Thom atop Mount Canobolas on a mild afternoon

Going west of the sandstone curtain is a rare event for me. The central west of NSW has long been an area outside my geographic range. So a recent visit with family and friends excited those old instincts of regional geographer to explore a landscape that has evolved over 400 million years since oceanic and marine forces added to the core of the Lachlan fold belt in the Palaeozoic.

Travelling by train to Orange gave us a chance to take in lands that have been transformed dramatically by geological events, the forces of fluvial dissection, deep chemical weathering and much later by human activities of First Nations people and then European explorers, some of which is found in the Regional Museum. Following the penetration of the Blue Mountains the rapid spread of graziers carved up the woodlands until the gold rush explosion of mining settlements in the valleys of the country around Bathurst and Orange. Our primary school history lessons started here with stories of Hargraves and the extraction of gold that got the bushranger “industry” active. As time moved on, established towns built their economies around a range of rural and manufacturing services as well as providing opportunities for education that continues today. For some of us from Sydney’s eastern suburbs they offered temporary refuge during the dangerous days of bombing in mid-1942.

What fascinated me this time was noting some of the more obvious landscape characteristics around Orange and what I could make of changes over the last century or so. This was a quick refresher course in geology, mining history, agricultural and urban change. The sight of the closed coal-fired power station at Wallerawang west of Lithgow alerted me to such change knowing that old munitions factories here had already gone. Industrial decline was evident in Bathurst and Orange where white goods and woollen mills once employed many locals. Abandoned mine shafts seen along the Mitchell Highway at Lucknow just east of Orange inform us of initiatives of former landowners such as the famed William Charles Wentworth. Today this is just a pleasant tourist stop. But Wentworth’s investment set the scene for decades of gold and other mines throughout the region, many now abandoned along with their little towns, while new ones flourish such as Cadia. Why is this so?

I looked in vain for the story of local geology and mining in the Orange Regional Museum (but there is an on-line site). But a trip out to Ophir in the hills north of Orange offered insights. Here is where Lawrence Hargraves and his tenants John Lister and William Tom Jr discovered alluvial gold in the local stream (Lewis Ponds Creek). A gold rush soon got underway. Gold was found three ways: in flowing streams, in Tertiary river gravels, and in quartz veins (“leads”) within the steeply dipping bedrock. Posters at the site of the abandoned mining village give some background to its history. Thomas Mitchell, the famous government surveyor, designed a street plan soon after discovery for the future town; it was interesting to see the name Tom spelt “Thom” on his plan. Sadly, all gold had gone before the streets were laid out.

Ophir provided a reason to look further at the geology and relate it to contemporary mining. Sydney University geologists have long-studied rocks of the Lachlan Fold Belt of the central west. Sandstones and shales to the east in the Blue Mountains were of lesser interest. I can see why now when you examine a geologic map and see how folded and faulted sequences of Palaeozoic age were subjected to igneous intrusion, metamorphic processes, and hydrothermal alterations. I learnt more about this on returning home. Details on the Cadia mine located to the south of Orange can be found in technical reports of Newcrest Mines and in a thesis by A.J. Wilson: The geology, genesis, and exploration context of the Cadia gold-copper porphyry deposits, NSW (PhD thesis, University of Tasmania, 2003). There was little publicity about Cadia in Orange. The mining is new, commencing in the 1990s; it required a supply of water that competed with town demands during the Millennial drought. In essence there is a deep open cut mine and the more recent “Ridgeway” underground mine. This lies 450m below the surface under a cap of Miocene basalts 20-80m thick. The story of mineralisation and discovery of these rich veins of gold makes fascinating reading.

Between 11 and 13M years ago volcanic activity took place in this region as the continent drifted north over a “hot spot”. This led to extrusion of lavas from numerous vents with varying lithologies and the formation of the shield volcanic feature known as Mount Canobolas. It is the highest feature between the Blue Mountains and Perth at 1395m and contains distinctive flora including an old favourite tree of mine, the snow gum, Eucalyptus pauciflora. It was magic to be at the top of this mountain at sunset on a calm warm evening knowing next day the temperature and wind chill would make it somewhat less pleasant.

Basalt sheets cover an ancient weathered palaeoplain that cuts across the folded, mineralised Palaeozoic rocks and locally has buried Tertiary river gravels. Soils formed on these basalts are very rich creating the basis for intensive horticulture, viticulture, and vegetable agriculture. It was a pleasure to visit a local vineyard and fig orchard (“Norland”). Although figs are grown in association with other fruit trees such as apples, this particular farm specialises in figs and uses waste fruit to feed a few cattle who regard figs like we do chocolates. The orchardist kindly provided details on operations as we explored his incredible mix of farm “junk” the likes of which I have never seen.

Travel to this district area offers a variety of other experiences. Scrambling around the Borenore caves formed in the Silurian reef limestone tested my wonky knee. It was a joy to be once again in a karst area, albeit quite small, and renew acquaintance with distinctive landforms and vegetation. We were in the Orange district during its food and wine festival along with many tourists happy to escape the bondage of Covid lockdowns The Orange food market was held in a manner free of Covid restrictions and offered specialities never before encountered: a gin stall, or a place to buy kangaroo bones for dogs being two. The contrast between the older tree-lined streets with their gorgeous autumn colours and classic federation-style homes, with the new cheek-by-jowl metal roofed housing estates was quite stark. Old and new, building decay or rejuvenation, changing economies yet continuing respect for its past, all was found in this lovely town.

Back on the train to the coast enjoying the grazing country on gently rolling hills and deep granitic weathered soils near Bathurst before encountering those familiar horizontal bedded Triassic rocks to the east. Up to Bell noting those fire-swept ridges and gorges of the western part of the Blue Mountains; such a contrast in natural disaster impact to that associated with the muddy recently flooded Nepean River. Quickly across the Cumberland Plain and western Sydney to the beautiful waters and shores of Sydney Harbour—back to one’s comfort zone!

Bruce Thom

Words by Prof Bruce Thom. Please respect the author’s thoughts and reference appropriately: (c) ACS, 2021. For correspondence about this blog post please email austcoastsoc@gmail.com

#188By Prof Bruce Thom | Sunday, April 25, 2021 |

Big surf at Port Fairy (Victoria) – April 2021

Big surf at Port Fairy (Victoria) – April 2021