CLIMATE CHANGE AND RELATIVITY – SOME PARALLELS

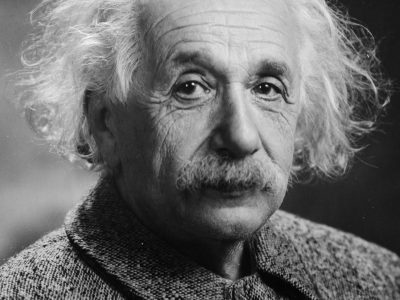

Albert Einstein 1920 (Source: Pixabay)

Science can be incomprehensible to many, yet it requires others to help communicate and apply great works such as those of Albert Einstein. Climate change science is also quite complex and those in this field are facing similar difficulties to those who sought to explain relativity to the broader public. It is irresponsible of decision-makers to not trust the science and ignore its implications in today’s uncertain world.

That the pursuit of science can be messy and at times chaotic can be seen in a recent book by Matthew Stanley entitled “Einstein’s War—how relativity conquered nationalism and shook the world”. In reading this work, I was struck by parallels between the process of developing and communicating the science around the Theory of Relativity during and immediately after World War One, and the acceptance and application of the science of climate change. Two very different areas of science, two different eras, but similar issues of acceptance by the broader community and the political class.

Albert Einstein rose from obscurity in war-ravaged Europe to world fame within a few years of the end of the Great War. His grand new vision of Physics was trapped behind the battle lines as he worked under very difficult personal and professional circumstances in Berlin. He was against the militarism of many of his science colleagues. However, his “thought” experiments and mathematics were exchanged with select colleagues in Germany. Through contacts in neutral Netherlands his work made its way to England. At this time strong anti-German sentiments prevailed in Anglo science. It was a nation full of bitterness for all its huge losses. Yet Arthur Eddington, Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge, and a Quaker/conscientious objector, managed to see the great need to understand and develop experiments to test Einstein’s theories. That he managed to do this is itself a story given the hate and anger of the times as well as intense opposition to new ideas that challenged those of the great national hero, Isaac Newton. Yet by the end of the war Eddington was able to gain support for expeditions to observe the 1919 solar eclipse that set out to test a key element of relativity, the deflection of light around the sun. To Eddington, science was international and not the preserve of patriotic self-interest.

Climate change science has evolved from international research endeavours to become politically complicated within and between nation states. Through the efforts of climate scientists in many countries, often with resource limitations, the world is better informed of its future if greenhouse gas emissions are not curbed. Establishment of the IPCC and through recurrent reports and meetings of scientists, policy makers should be aware of the consequences of global warming. It is a huge political issue. For many the future of the planet is at stake.

Difficulties facing those confronted with complex science, whether it is relativity or climate change, are similar. To many the specifics of the mathematics that support the predictions/projections are incomprehensible. We must trust those who have the skills and who are funded to deliver the knowledge. This is not easy as much of what science tells us does not meet the common-sense test of what is “real”. But science offers us powerful new ways to learn about the world around us and in so doing also provides ways to find solutions. Relativity and climate change have benefited from improved techniques and built on lessons learnt from initial experiments, observations and models designed to verify the “reality” of the ideas. Consultation with colleagues offer the best way to develop these tests, and in both cases, we see advances in knowledge through scientific debates on theories and data used to test the theories.

What is clear from reading Stanley’s book on Einstein is the importance of a powerful advocate in communicating the science to the broader community. This was the case with Huxley and his articulation of Darwin’s evolution. For Einstein it was Eddington. It was not easy in either case, and that remains true of climate science. We are often quick to pounce on “errors” and then dismiss the main thrust of the new science. Improvements in understanding require continued investment in the science itself, despite antagonism from certain quarters. But informed scientists must communicate to the public. Here is where sustained political advocacy is required in the spirit of Huxley and Eddington for their respective giants of science.

As Bob Hawke said at the time of the First Prime Ministers Science Council in 1989, climate change may involve changing patterns of behaviour by society. That is happening today in some island nations. Our climate scientists have now a much clearer understanding of what we can expect compared to what we said at that Council meeting in 1989. Yes, at times the science looks messy, but it is meaningful and needed. It is totally irresponsible in today’s world to be ignored and not trusted.

Bruce Thom

Member Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists.

Words by Prof Bruce Thom. Please respect the author’s thoughts and reference appropriately: (c) ACS, 2019, for correspondence about this blog post please email austcoastsoc@gmail.com

#143

DOUGLAS W. JOHNSON 1919 AND BEYOND

DOUGLAS W. JOHNSON 1919 AND BEYOND